Advertisement

matter

In an ambitious international collaboration, researchers have “mapped” proteins in the coronavirus and identified 50 drugs to test against it.

Working at a breakneck pace, a team of hundreds of scientists has identified 50 drugs that may be effective treatments for people infected with the coronavirus.

Many scientists are seeking drugs that attack the virus itself. But the Quantitative Biosciences Institute Coronavirus Research Group, based at the University of California, San Francisco, is testing an unusual new approach.

The researchers are looking for drugs that shield proteins in our own cells that the coronavirus depends on to thrive and reproduce.

Many of the candidate drugs are already approved to treat diseases, such as cancer, that would seem to have nothing to do with Covid-19, the illness caused by the coronavirus.

Scientists at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York and at the Pasteur Institute in Paris have already begun to test the drugs against the coronavirus growing in their labs. The far-flung research group is preparing to release its findings at the end of the week.

There is no antiviral drug proven to be effective against the virus. When people get infected, the best that doctors can offer is supportive care — the patient is getting enough oxygen, managing fever and using a ventilator to push air into the lungs, if needed — to give the immune system time to fight the infection.

If the research effort succeeds, it will be a significant scientific achievement: an antiviral identified in just months to treat a virus that no one knew existed until January.

“I’m really impressed at the speed and the scale at which they’re moving,” said John Young, the global head of infectious diseases at Roche Pharma Research and Early Development, which is collaborating on some of the work.

“We think this approach has real potential,” he said.

Some researchers at the Q.B.I. began studying the coronavirus in January. But last month, the threat became more imminent: A woman in California was found to be infected although she had not recently traveled outside the country.

That finding suggested that the virus was already circulating in the community.

“I got to the lab and said we’ve got to drop everything else,” recalled Nevan Krogan, director of the Quantitative Biosciences Institute. “Everybody has got to work around the clock on this.”

Dr. Krogan and his colleagues set about finding proteins in our cells that the coronavirus uses to grow. Normally, such a project might take two years. But the working group, which includes 22 laboratories, completed it in a few weeks.

“You have 30 scientists on a Zoom call — it’s the most exhausting, amazing thing,” Dr. Krogan said, referring to a teleconferencing service.

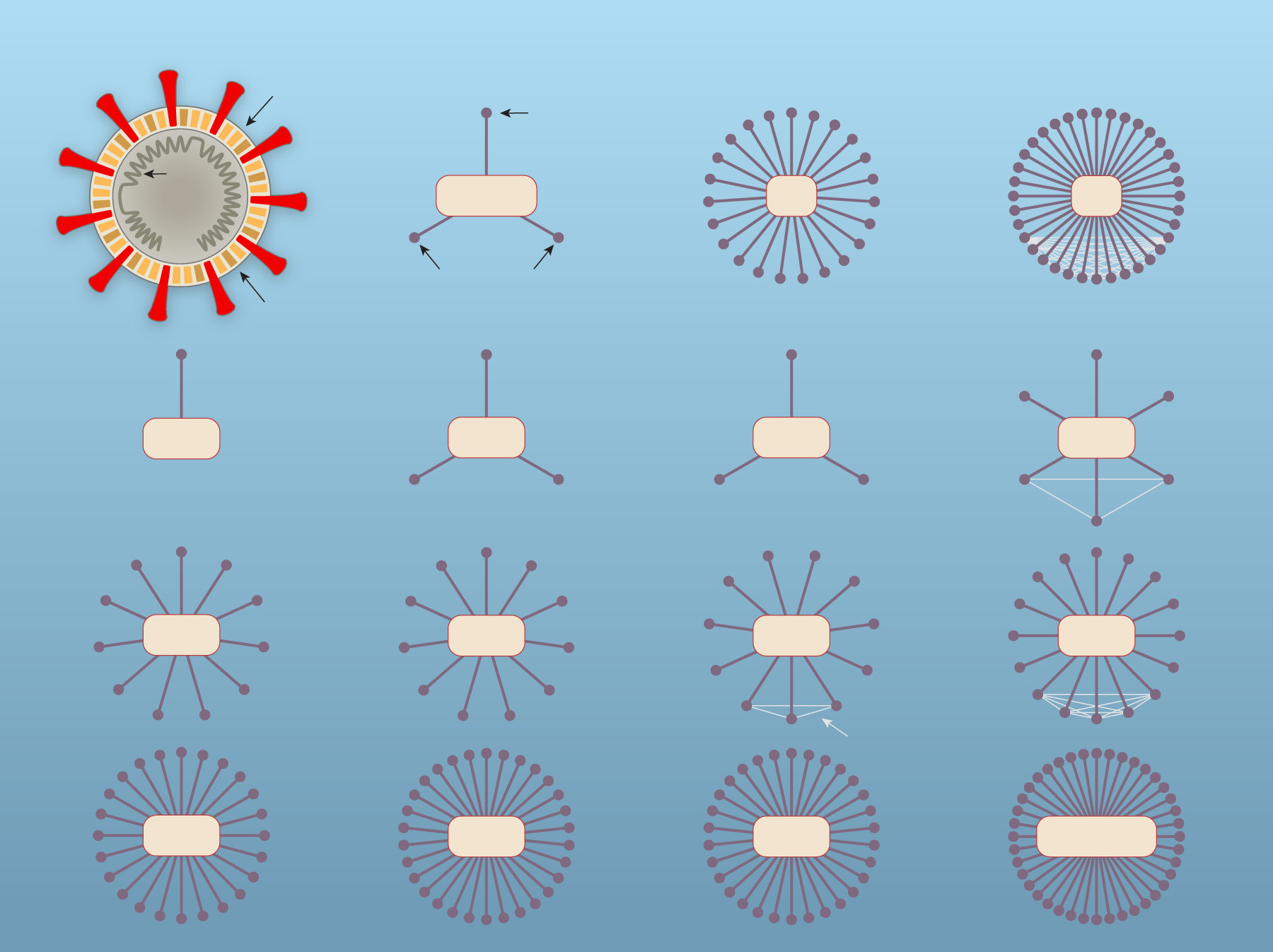

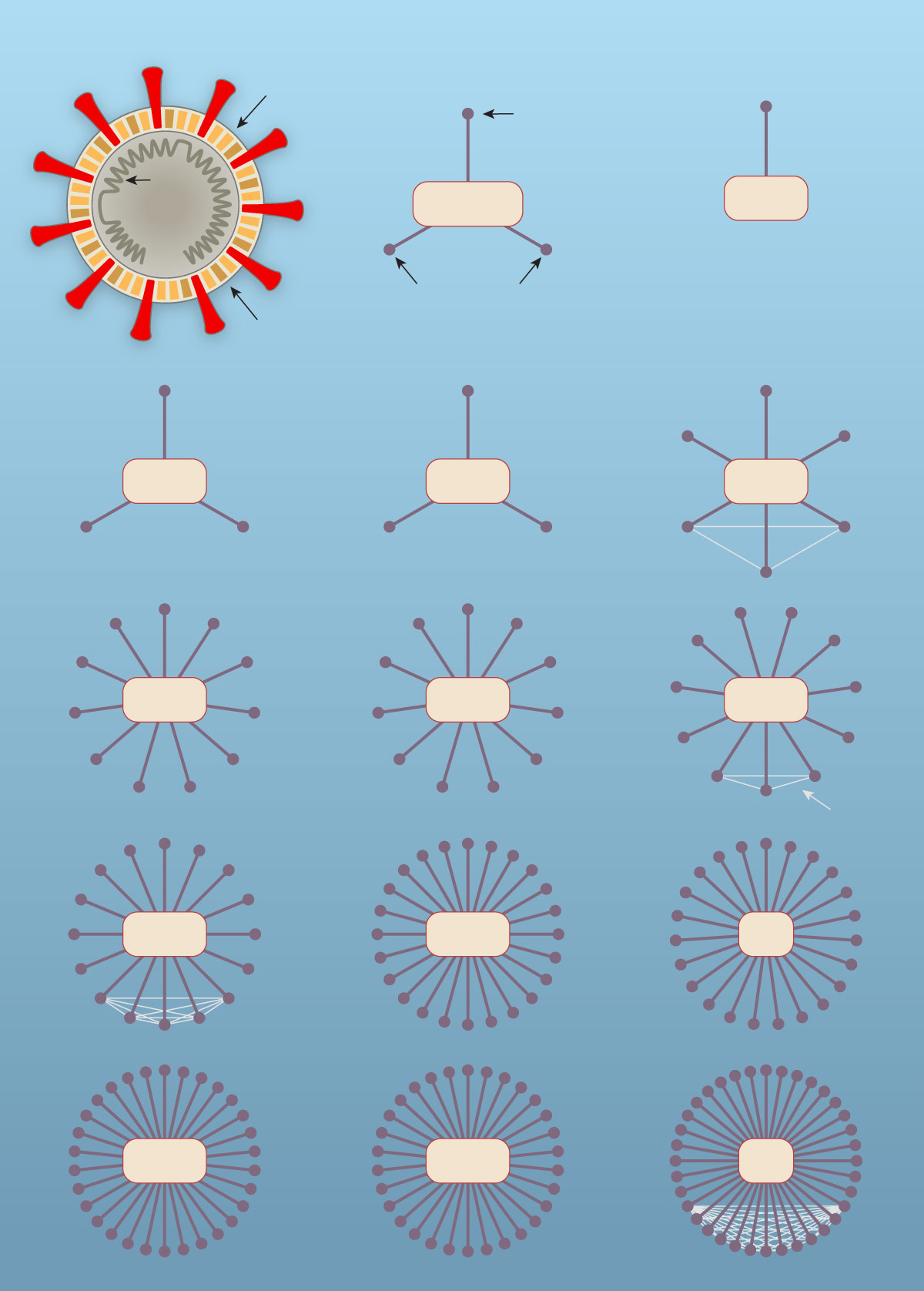

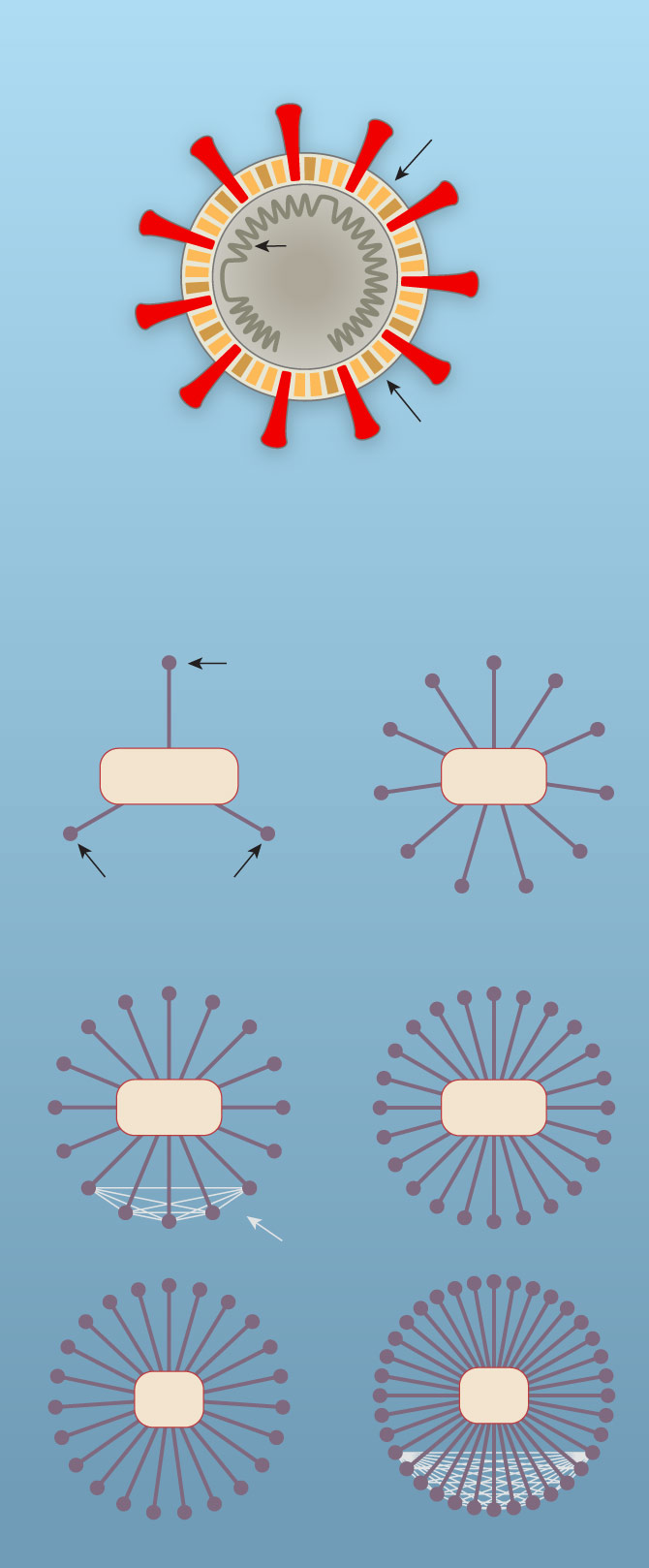

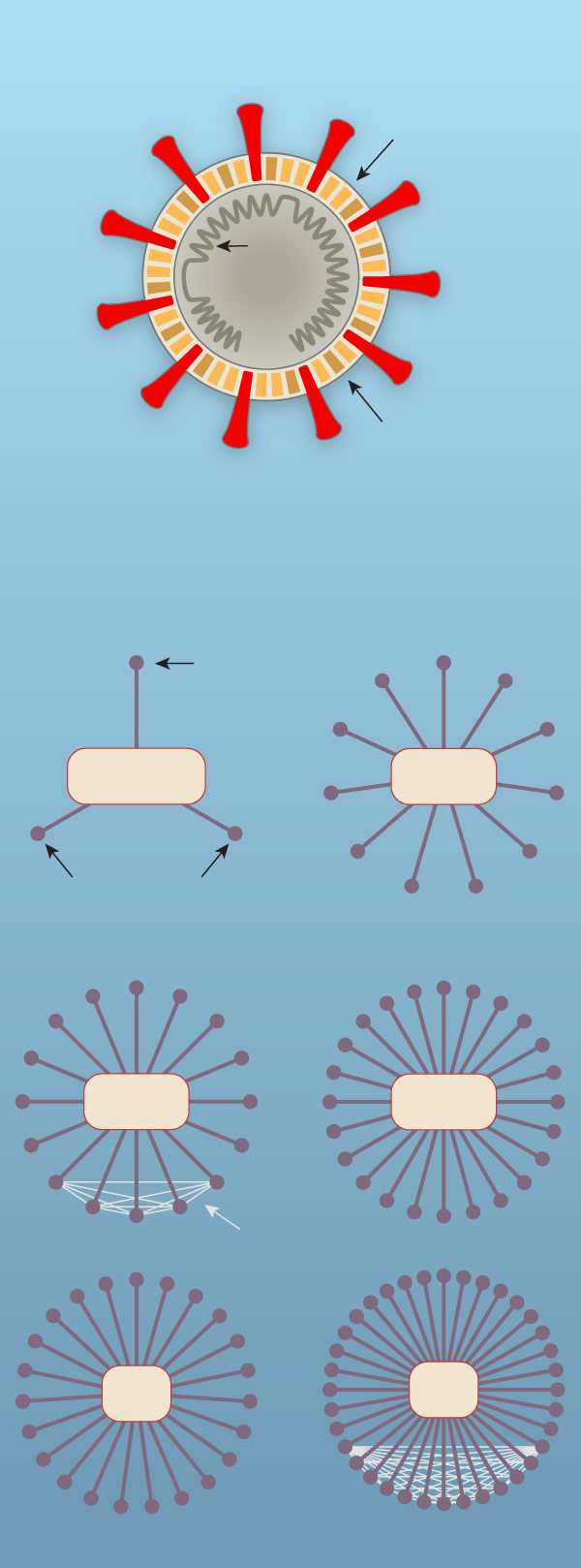

Viruses reproduce by injecting their genes inside a human cell. The cell’s own gene-reading machinery then manufactures viral proteins, which latch onto cellular proteins to create new viruses. They eventually escape the cell and infect others.

In 2011, Dr. Krogan and his colleagues developed a way to find all the human proteins that viruses use to manipulate our cells — a “map,” as Dr. Krogan calls it. They created their first map for H.I.V.

That virus has 18 genes, each of which encodes a protein. The scientists eventually found that H.I.V. interacts, in one way or another, with 435 proteins in a human cell.

Dr. Krogan and his colleagues went on to make similar maps for viruses such as Ebola and dengue. Each pathogen hijacks its host cell by manipulating a different combination of proteins. Once scientists have a map, they can use it to search for new treatments.

In February, the research group synthesized genes from the coronavirus and injected them into cells. They uncovered over 400 human proteins that the virus seems to rely on.

The flulike symptoms observed in infected people are the result of the coronavirus attacking cells in the respiratory tract. The new map shows that the virus’s proteins travel throughout the human cell, engaging even with proteins that do not seem to have anything to do with making new viruses.

One of the viral proteins, for example, latches onto BRD2, a human protein that tends to our DNA, switching genes on and off. Experts on proteins are now using the map to figure out why the coronavirus needs these molecules.

Kevan Shokat, a chemist at U.C.S.F., is poring through 20,000 drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration for signs that they may interact with the proteins on the map created by Dr. Krogan’s lab.

Dr. Shokat and his colleagues have found 50 promising candidates. The protein BRD2, for example, can be targeted by a drug called JQ1. Researchers originally discovered JQ1 as a potential treatment for several types of cancer.

On Thursday, Dr. Shokat and his colleagues filled a box with the first 10 drugs on the list and shipped them overnight to New York to be tested against the living coronavirus.

The drugs arrived at the lab of Adolfo Garcia-Sastre, director of the Global Health and Emerging Pathogens Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital. Dr. Garcia-Sastre recently began growing the coronavirus in monkey cells.

Over the weekend, the team at the institute began treating infected cells with the drugs to see if any stop the viruses. “We have started experiments, but it will take us a week to get the first data here,” Dr. Garcia-Sastre said on Tuesday.

The researchers in San Francisco also sent the batch of drugs to the Pasteur Institute in Paris, where investigators also have begun testing them against coronaviruses.

If promising drugs are found, investigators plan to try them in an animal infected with the coronavirus — perhaps ferrets, because they’re known to get SARS, an illness closely related to Covid-19.

Even if some of these drugs are effective treatments, scientists will still need to make sure they are safe for treating Covid-19. It may turn out, for example, that the dose needed to clear the virus from the body might also lead to dangerous side effects.

This collaboration is far from the only effort to find an antiviral drug effective against the coronavirus. One of the most closely watched efforts involves an antiviral called remdesivir.

In past studies on animals, remdesivir blocked a number of viruses. The drug works by preventing viruses from building new genes.

In February, a team of researchers found that remdesivir could eliminate the coronavirus from infected cells. Since then, five clinical trials have begun to see if the drug will be safe and effective against Covid-19 in people.

Other researchers have taken startling new approaches. On Saturday, Stanford University researchers reported using the gene-editing technology Crispr to destroy coronavirus genes in infected cells.

As the Bay Area went into lockdown on Monday, Dr. Krogan and his colleagues were finishing their map. They are now preparing a report to post online by the end of the week, while also submitting it to a journal for publication.

Their paper will include a list of drugs that the researchers consider prime candidates to treat people ill with the coronavirus.

“Whoever is capable of trying them, please try them,” Dr. Krogan said.